Poetry has the capacity to be so much more than just beautiful.

It can be scathing, fierce. It can build empathy, act as a shelter, help us survive. And it can be a vehicle for responding to oppression.

Cue erasure.

Erasure is a tool people in power use to cause real and lasting harm.

But poets can wield erasure too. At the end of this post I’ll challenge you to create an erasure poem that responds to oppressive erasure.

Erasure is a weapon often wielded by rich, powerful white men.

I make a modest living as a freelance editor. A week ago, while editing a public-facing medical article about intimate partner violence, or IPV, I needed to update the statistics it cited. I turned to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) webpage on IPV that included details about which groups are most at risk of experiencing IPV.

Here’s what the webpage said back in May 2024 (I used the Wayback Machine to find a historical version of the site):

While violence impacts all people, some individuals and communities experience inequities in risk for violence due to the social and structural conditions in which they live, work, and play. Youth from groups that have been marginalized, such as sexual and gender minority youth, are at greater risk of experiencing sexual and physical dating violence. [emphasis mine]

Here’s what the website says now:

While violence impacts all people, some individuals and communities experience inequities in risk for violence due to the social and structural conditions in which they live, work, and play. Youth from groups that have been marginalized are at greater risk of experiencing sexual and physical dating violence.

The CDC erased seven words, due to the recent executive orders commanding all federal websites to purge themselves of the mention of transgender people.

The CDC had also removed their associated Report on Intimate Violence that uses carefully gathered datasets to summarize “the lifetime and 12-month experiences of victims of intimate partner violence in the United States.”

Nothing’s changed since last week—it’s still gone:

Whether it’s in health research data or on the football field (the NFL erased the end zone message “END RACISM” for the Super Bowl), wide-scale erasure is happening with unusual speed.

Erasure can be brutally powerful.

Take the IPV report data. First and foremost, erasing this data means that human beings—many of them children—may not be able to access or benefit from preventive, protective, therapeutic, or legal help. Erasing the official humanity and existence of a group of human beings can doom them to exist in shadows, outside the protection of civil society, outside the protection of the law.

Those who commit IPV against transgender people may be able to hide their horrific acts—if trans folks don’t show up in the data, there’s no reason to believe they’re even real; why punish someone for harming an imaginary person?

It sounds preposterous to me even as I write it, but this is ultimately what we’ve come to. It’s not new—we’ve seen violence and murders go unpunished because of the LGBTQ+ “panic” defense—but it’s being made brazenly official, recently.

Perhaps it’s worth noting the obvious: Violent people who hurt or murder other human beings are a danger to everyone in society.

Erasure can be subtle, and emotionally controlling.

Both dictators and your run-of-the-mill generic abusers know how to shift reality by removing and replacing words and meanings. They know how to structure policies and messages to elicit specific behaviours or mindsets in their target audience. Gaslighting, anyone?

Corporations use the power of words to spin touching yarns to sell cars and burgers and diapers. Who among us hasn’t involuntarily teared up just a little at the heartstring-tugging scripting of a carefully crafted commercial? As the writers of those commercials go through their initial drafts, they meticulously erase anything that doesn’t serve their purpose.

Take the recent Super Bowl commercial starring Harrison Ford. To sell vehicles, the writers crafted a monologue that carefully excludes all mention of anything other than vague, middle-of-the-road ideals. By cutting out any mention of anything remotely upsetting to anyone, they avoided being lumped in with the “woke” folks or the “MAGA” folks, since they hope to sell more of their products to everyone.

And in doing so they created an utterly meaningless but strangely moving piece of tripe that accomplished precisely nothing. It’s vapid, meaningless, patriotic flag-waving that subtly implies that everything’s fine, everything’s gonna be okay, why not spend some money?

But it’s not fine, it’s not going to be okay. We must make better art than that produced by advertisers. We cannot walk a narrow, compassionless middle road, side by side with people who are actively oppressing us, our friends, and our neighbours.

I know it’s hard to know what to do as poets, now or at any point in history, to push back against these forms of power. I’m here to suggest you try one small, resolute, poetic act. Read on about erasure poetry and simple instructions for an erasure poetry project.

Poets can wield the power of erasure.

Most poets don’t have the reach and the scope of the government or a celebrity, nor the audience of a journalist or filmmaker.

But that doesn’t mean we’re powerless. As the (West African, as far as I can tell) proverb goes, “If you think you're too small to make a difference, try spending the night in a closed room with a mosquito.”

What is erasure poetry?

Erasure is a poetic form in which a poet creates a new poem by altering a pre-existing text through omission, cutting, crossing out, whiting out, blacking out, painting, and so on. What remains becomes a new poem made out of parts of the original text.

Erasure poetry has a rich literary history. Let’s do a very brief survey of some of the ways poets have used this form.

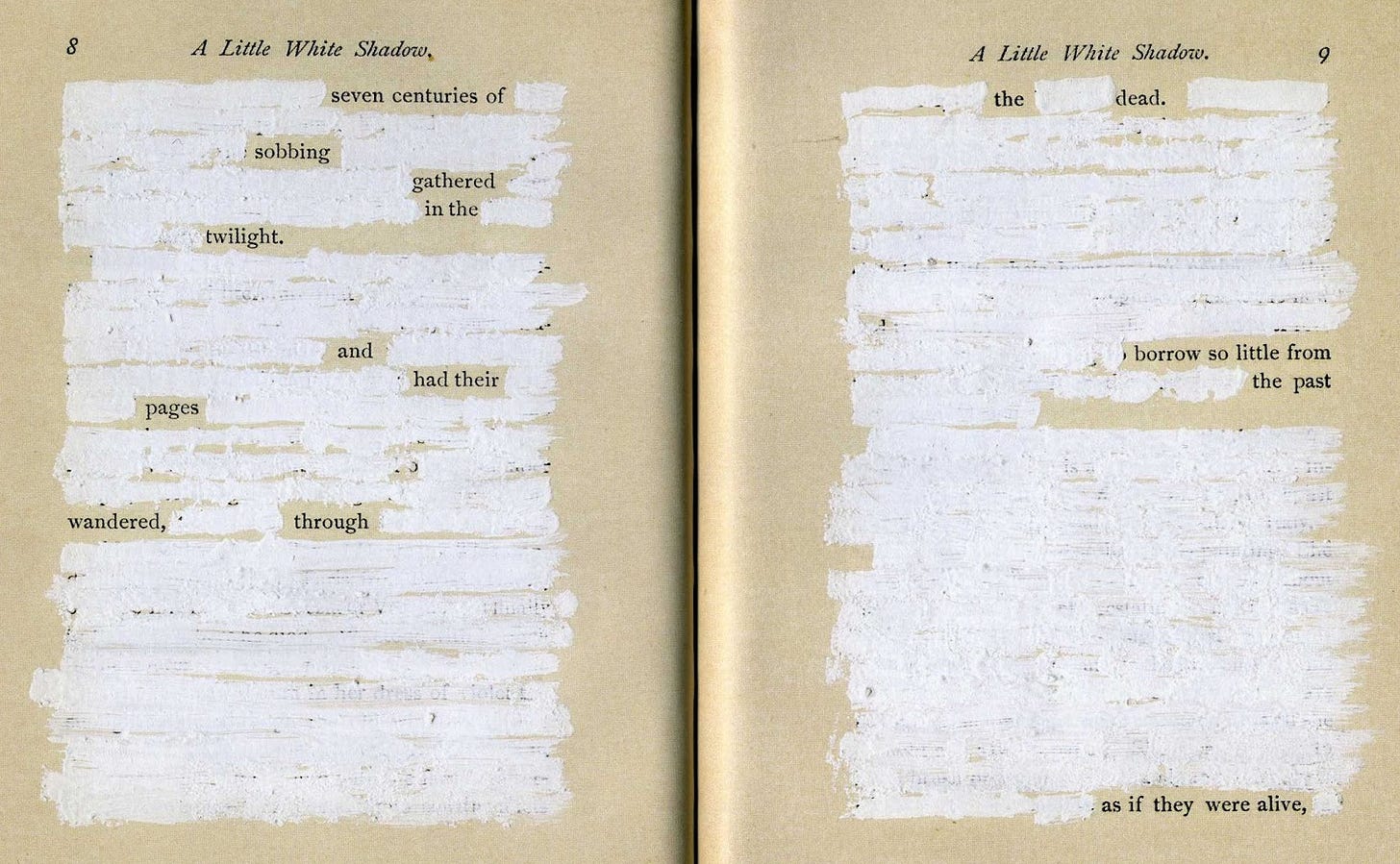

Many poets have employed erasure as a tool to make fun or pretty poems. Below is an excerpt of Mary Ruefle’s book, A Little White Shadow. Reviews of the book use words like “arbitrary” “enchanting” “specialness” and “intimacy,” reflecting its quirky, playful nature.

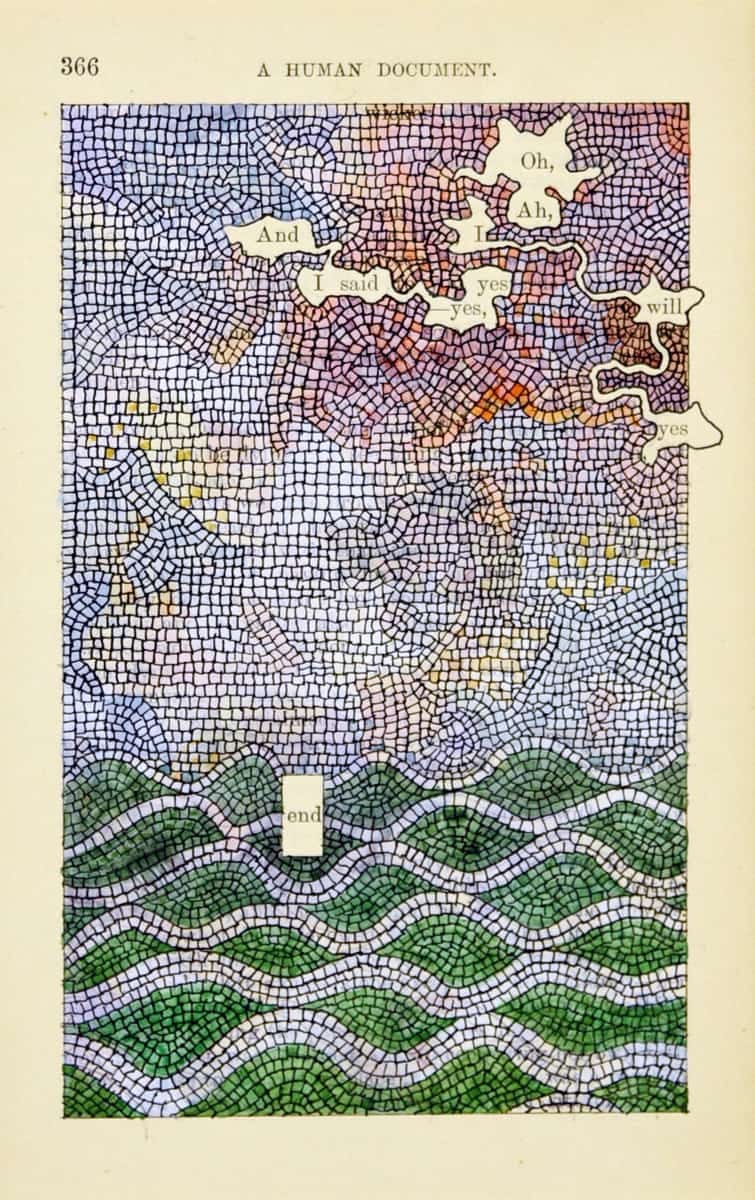

Tom Phillips’ book, A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel, dives into the form’s potential for pure visual pleasure. Reviews of the book include words like “strange,” “beguiling,” “amazing,” and “beautiful.”

As fun as this use of erasure is—and I do love being playful while creating—it’s also like dressing up a dragon in a tutu and chaining her to a mountain.

Because, as I hope I’ve made clear, erasure is a powerful beast.

Erasure poetry can reframe false, unjust, and cruel narratives, honour the harmed, and/or dishonour the ones who cause harm.

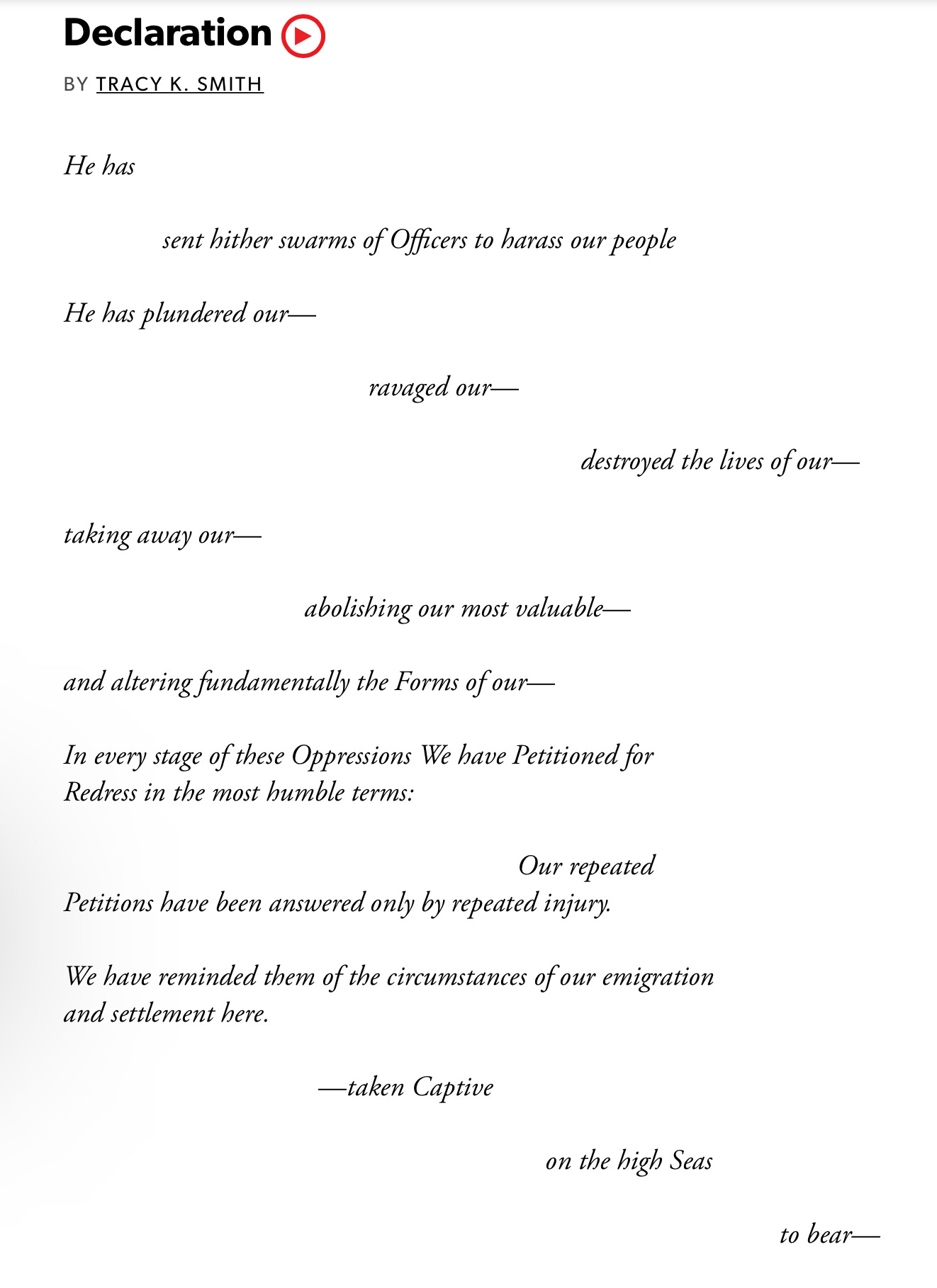

In the book Wade in the Water, former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith, reworks the Declaration of Independence in the poem “Declaration.” In an interview (found at the bottom of the poem’s page I’ve linked to), she explains that when reviewing the Declaration of Independence, she arrived at the section that speaks to the grievances against England, and she felt “that they were speaking so clearly to the history of Black life in this country.” She deleted parts of the document until she had produced her erasure poem centring the Black experience in the United States.

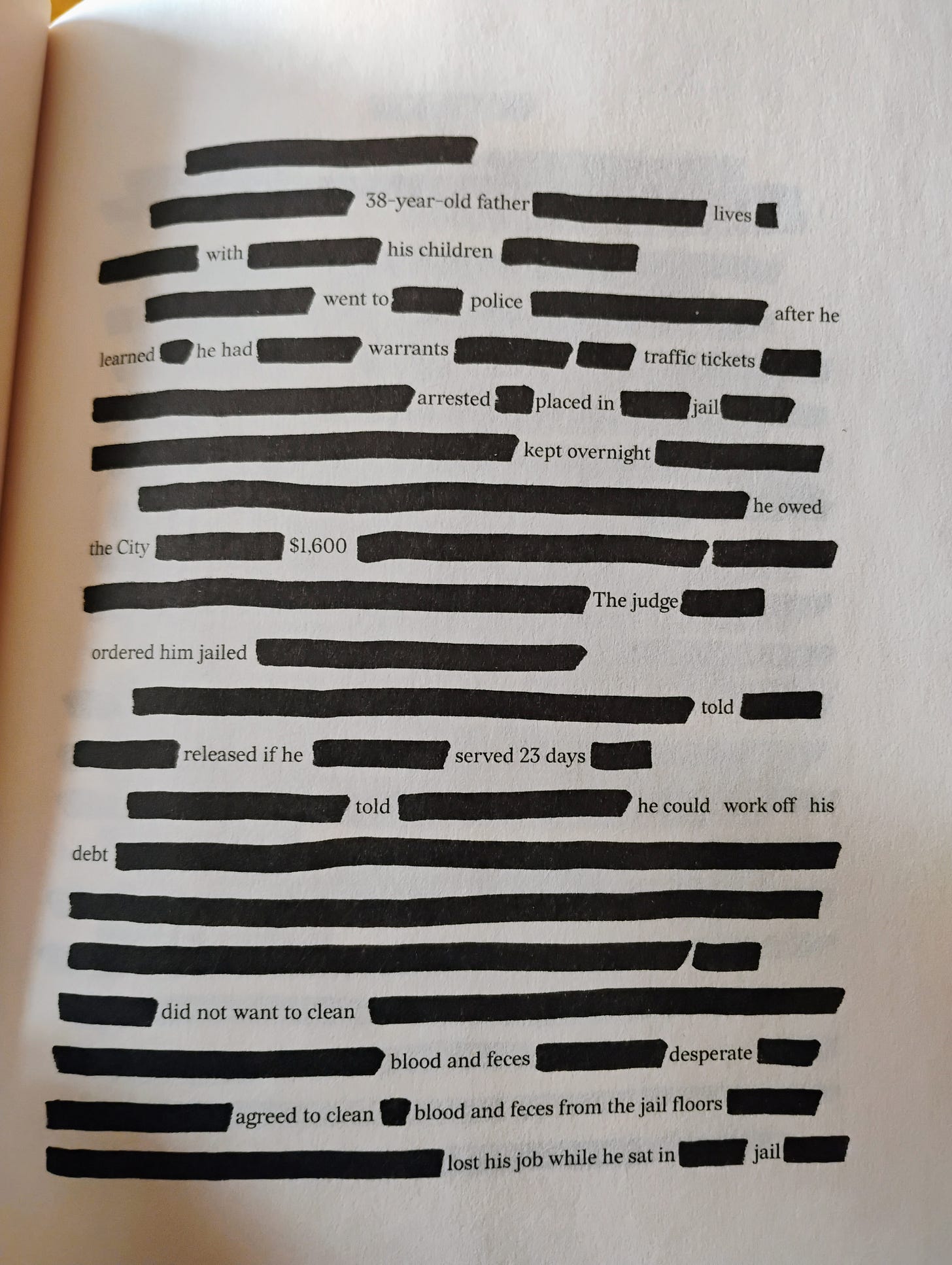

In his book Felon, poet, lawyer, and MacArthur Fellow Reginald Dwayne Betts includes many erasure poems he made using court documents centred around the ways impoverished people are punished for their poverty.

For example, a person who cannot afford to pay a traffic ticket can be sent to prison and charged bail which they also cannot afford to pay. Here’s an excerpt of the erasure of one page of a court document in the poem “In Alabama.”

Reviews of both these books speak of their power, their testimony, and their invitation to practice empathy. These poems aren’t there for our entertainment. These poems shake the moss off our faces and wake us up. They fling shame off the backs of the oppressed and into the laps of the real culprits.

These poets—and so many other brilliant writers—light a path for the rest of us.

Let’s make some erasure poetry.

This week I saw a fleeting Instagram Story posted by the witty and fierce Jameela Jamil. Folks had asked her why she wasn’t putting out responses to specifically denounce this or that man in the current administration.

She responded by pointing out that those men are narcissists, and what they want more than anything is to be spoken about, regardless of whether it’s condemnation or praise.

Most of us, myself included, haven’t been able to keep from supplying their narcissistic hunger with our attention. It’s so enthralling, dramatic, horrific.

But where do we look, if not at those men?

We look at who they’re targeting.

We affirm the existence and the humanity of those they’re oppressing.

We centre those who are being actively erased.1

Challenge:

Use erasure to restructure and repurpose an oppressive, harmful text.

Choose a source text that erases or oppresses trans folks, people of colour, immigrants, refugees, women, or any other group. You might choose an executive order, a speech, an interview, an op-ed, a court order, or an article featuring the words, ideas, or commands of the oppressor of your choice.

NOTE: Don’t choose the words of someone from a minority or oppressed group to which you don’t belong. Most obviously: white folks, don’t erase Black folks’ voices, no matter who they are or what they may have done. Just don’t. There are plenty of white folks for us to focus on.Physically or digitally erase the words and/or letters strategically until there’s no mention of the people who are advocating for or enacting the harm.

Embrace and centre the very people whom the text sought to oppress and render invisible, so all that’s left are words that redirect the reader’s attention away from attention-seeking, racist, sexist, ableist, classist, colonizing, transphobic narcissists and toward the causes and humans who actually need our attention.If you feel able to, post your creation to social media. Invite others to join by using the hashtags #erasurepoem and #antierasure and #erasetoembrace and anything else you think is apt and useful.

Thank you to whomever posted a call on social media for news articles to stop using photos of certain rich and powerful white men, and to instead use photos of the people whom those men’s policies, proclamations, and actions will affect. I don’t remember whose post it was and can’t find it now, but it helped me shift my focus and find a path forward this week. Thanks also to my brilliant partner, who helped me design this poetry challenge.

THIS: But where do we look, if not at those men?

We look at who they’re targeting.

We affirm the existence and the humanity of those they’re oppressing.

We centre those who are being actively erased.

I am regularly impacted by your approach to seemingly difficult, contentious topics. You are neither combative, nor judgmental, simply passionate, openhearted and challenging (even a bit angry in this one). You provide guidance, for me anyway, on how to constantly reexamine how I wish to show up in the world, my convictions and what I hold dear, which have changed over time, and especially this past year. Thank you.