I recently received a suggestion from a reader (thank you, Kate!) to write about interpunction, or the insertion of punctuation marks into a piece of writing. This wonderful suggestion has opened the flood gates! So beware, here begins an extra nerdy series.

I’ll start with some of the most exciting punctuation marks (to me anyway): the hyphen and en dash, and the beautiful, flexible em dash.

Hyphens and en dashes!

The hyphen (-) started out life connecting words that had been disconnected by enjambment (when the end of a line breaks up a word):

Please buy this incred- ible product I’m selling!

Nowadays, it's also used for compound words ("brother-in-law"), compound adjectives ("user-friendly") and fractions ("one-seventeenth").

Compounds

Hyphens are a wonderful way to build creative compound words (though you can also just stick them completely together in the German style; if we can have foghorn, then why not cookiepearl or goatpurse or filmsteward?).

Medbh McGuckian uses the hyphen to great advantage in this way—as in the poem “Birds, Women and Writing” with “word-bird,” “wasp-orchid” and “woman-chair.”

English translations of Icelandic kennings also excel at these combinations, rendering a beer as a “honey-wave” or “the brook of the cheer-cup.”

Hyphens can also bring together more than just two words, like e.e. cummings’ “busying-roundly-distinct”.1

Hints and subtleties

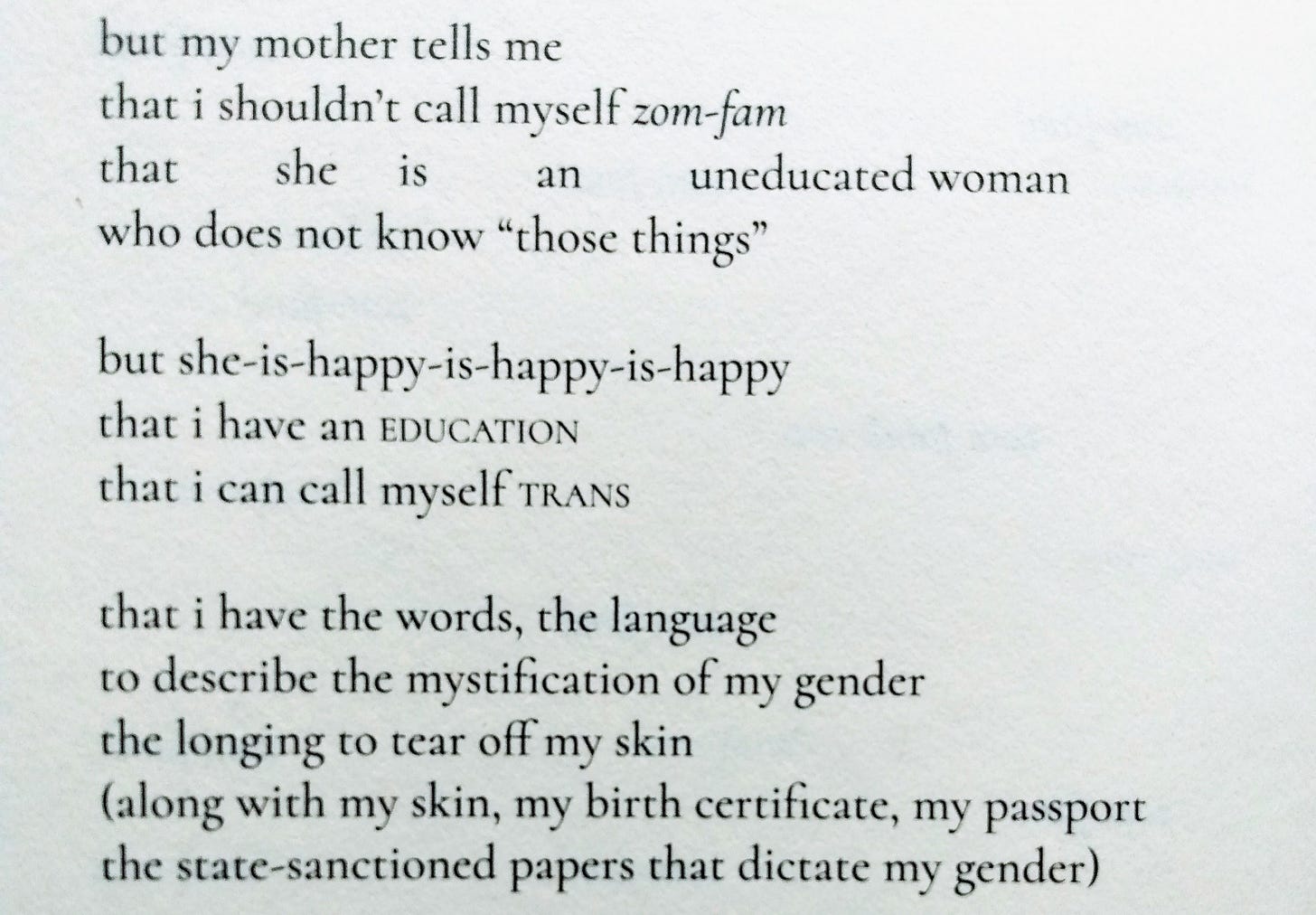

Kama La Mackerel uses a variety of dashes in their book Zom-Fam (2021), including the hyphen. In this excerpt below, it perhaps acts on the text as a hint of the-lady-doth-protest-too-much; OR perhaps as a tumbling—an input of speed and exhilaration (or both?):

En dashes

An en dash (–) is slightly longer than the hyphen. In everyday prose writing, it’s usually used for spans or ranges ("Jan–March" "1779–1979") but it can also be used like a hyphen (“bold–faced”).

Stand-ins

The en dash (as well as the hyphen) can stand in for missing text, like here, in an excerpt of Terrance Hayes’ poem “Who Are The Tribes” from the book How to be Drawn (2015):

Em dash!

The em dash (—) is the longest of the three horizontal lines, and it’s got so many everyday uses:

To symbolize a sudden pause or break:

Wait—what did you say?!To act as a bridge when a sentence structure suddenly changes:

Jose was glad, but Ali—he was elated.As a zestier parentheses, swinging the reader’s focus briefly away—like an "aside" in speech—and onto a group of words inside a statement or question.

To help make a sentence less awkward in cases where there are already a lot of commas:

When her mother got the phone call which had so vexed her, she’d thrown her apple onto the kitchen floor, and the dog had run to it—or really slid to it, since the floor had just been waxed.To lend a more casual or emphatic air to a place where otherwise a more formal, calmer colon (:) might be used:

Madison loves two foods—cloves and rhubarb.

But the em dash is flexible, and has many subtler uses—and it’s open for business if you’d like to hire it to do something completely new and creative.

Dickinson

Em dashes are famous for being one of the poet Emily Dickinson's favorite punctuations:

Because I could not stop for Death— He kindly stopped for me— The Carriage held but just Ourselves— And Immortality.

Her first editors famously removed these em dashes initially, to be restored by later, wiser generations. There is a great deal of literary discussion out there about her dash-craft, well-worth diving into, but ultimately the takeaway is she was bold with her dashes, she used them for many purposes both practical and subtle, and we all reap the benefits from her trailblazing in English poetry.

Practicalities

Em dashes can be handy as a sort of introductory moment in a poem, after which can follow an elaboration. In other words, they help text become a sort of subtitle. Dora Malech’s poem “Can’t Get There From Here”—from the book Say So (2011)—begins with the first line:

On car trips, word games—

The two verses that follow this line flow out from that car-based scene-setting; the first is directly related, the second a tangent.

Then the third and final verse of the poem begins with a line that switches the scene, employing once again an em-dash:

Flight and in-flight meals, condiments, commitment—

After which she expands into the word- and idea-worlds of flight and airplanes. It’s a highly useful employment of the em dash.

Asides

In Deaf Republic (2019), Ilya Kaminsky uses the em dash in a classical and almost theatrical way, as both emphasis and aside. An excerpt from “As Soldiers March, Alphonso Covers the Boy’s Face with a Newspaper” (though this excerpt is repeated elsewhere in the book too):

Observe this moment —how it convulses—

Another excerpt, this one from Kaminsky’s poem “Soldiers Aim at Us”:

They fire as the crowd of women flees inside the nostrils of searchlights —may God have a photograph of this— in the piazza's bright air, soldiers drag Petya's body and his head bangs the stairs. I feel through my wife's shirt the shape of our child.

Subtleties

For one example of a more subtle effect, let’s look to the book Felon (2019) by Reginald Dwayne Betts. In the poem “For a Bail Denied,” Betts uses the em dash to further offset a quote. It’s already rendered in italics, but the em dashes heighten the effect:

I am not his father, just a public defender, near starving, here, where the state turns men, women, children into numbers, seeking something more useful than a guilty plea & this boy beside me's withering, on the brink of life & broken, & it's all possible, because the judge spoke & the kid says —I did it I mean I did it I mean Jesus— someone wailed & the boy's mother yells: This ain't justice. You can't throw my son into that fucking ocean. She meant jail.

The em dashes here hint at the way the boy’s voice is almost an interjection, rather than a response. It’s interesting to see also how the em dashes help set the boy’s voice adrift, and separate it with literal bars from the rest of the poem/the courtroom/the world. Notably, the mother’s voice does not use em dashes, just italics. She’s in the world, connected—but also separated, horribly, from her son.

And

Em dashes don’t have to be limited to typesetter’s sizes. In their book Zom-Fam (2021), Kama La Mackerel takes the em dash and extends it to more aptly suggest a cosmic scale:

I’ve only offered the barest of overviews here… I could write a book on the em dash’s million uses in poetry. But instead, I’ll throw it back to you—and encourage you to give dashes a try.

Challenge:

Write a ten-line poem using two of the three types of dashes (or all three if you’re feeling particularly adventurous). You can use them in any way you’d like, but I’d encourage you to try using them in ways that are wholly new to your writing practice.

If you are struggling, I find that thumbing through others’ poetry (your own collection of books, or a collection at your local library or bookstore, or a virtual collection like that housed by ) can really help with ideas.

Coming up, I’ll be looking at other uses of punctuation in poetry, including dots (period, ellipsis), brackets, footnotes, strikethroughs, quotation marks, slashes, and more. I’ll also look at poem forms that evade & avoid punctuation, like one-sentence poems and poems that abstain entirely.

If punctuation isn’t up your alley, don’t worry—in between these hyper-nerdy topics I’ll be giving you breaks with lots of other topics.

Quote is from poem beginning “emptied.hills.listen” on page 438 of the PDF of his Complete Poems (1913-1962).

Excellent, unsurprisingly.

Two notes:

One. The en dash as a stand-in for missing text. In transcriptions of epigraphic, papyrological, and manuscript texts, breaks in the physical medium (whether complete absence, or simply totally obscuring abrasion, for instance) are marked with [square brackets]. If the text is reconstructable it will simply be written (squa[re br]ackets). If the letters have a regular width such that the number missing is relatively secure, they are written with ..., one for each letter (squa[.....]ackets). If however there's no way of knowing how many letters are missing, the en-dash appears on the scene (squa[- - - ).

Of course Carson, in her Sappho, limits herself to brackets and lets the absence speak for itself.

Two. In the last quotation, the extended dashes not only give a cosmic scale, they also mimic the continuous shirorekha line of the Devanagari script used to write Sanskrit.

I love hypens and dashes!