First, three quick announcements:

Chapbook \ Anthology \ Hugo House Class

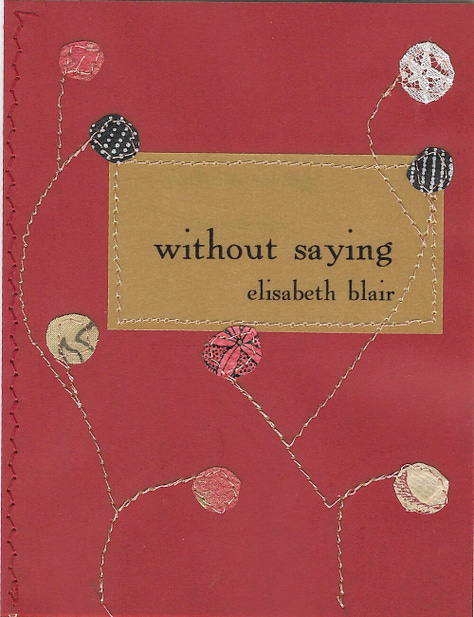

CHAPBOOK: My chapbook without saying (2020) has had a second printing—so it’s available again for $10 over at the amazing Ethel Press.

ANTHOLOGY: Billy-Ray Belcourt, Anne Carson, Tolu Oloruntoba… and somehow, myself?! I’m honoured to be one of the 50 poets included in Best Canadian Poetry 2025.

HUGO HOUSE: I’m teaching online through Seattle’s Hugo House in 2024-25! It’s called “Poetry Revision Mentorship” and it’s super hands-on with lots of feedback.

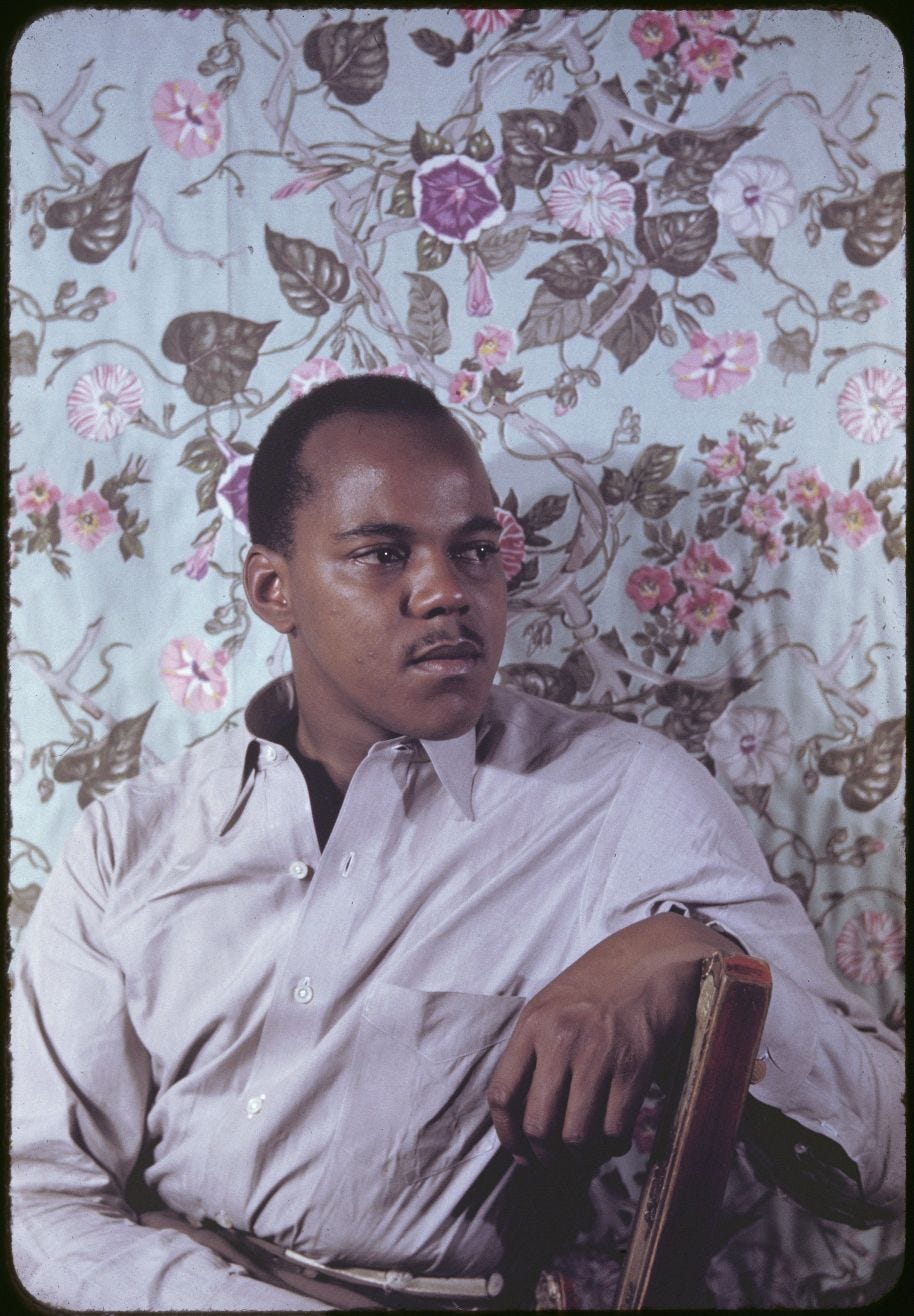

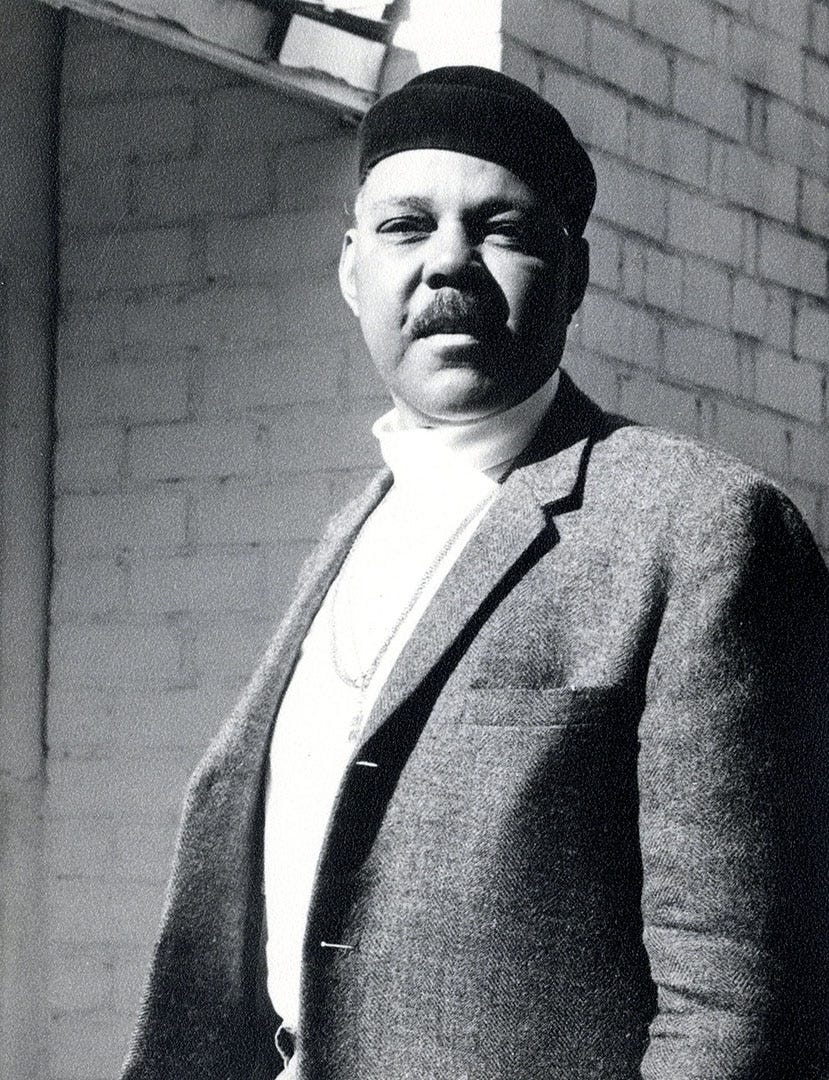

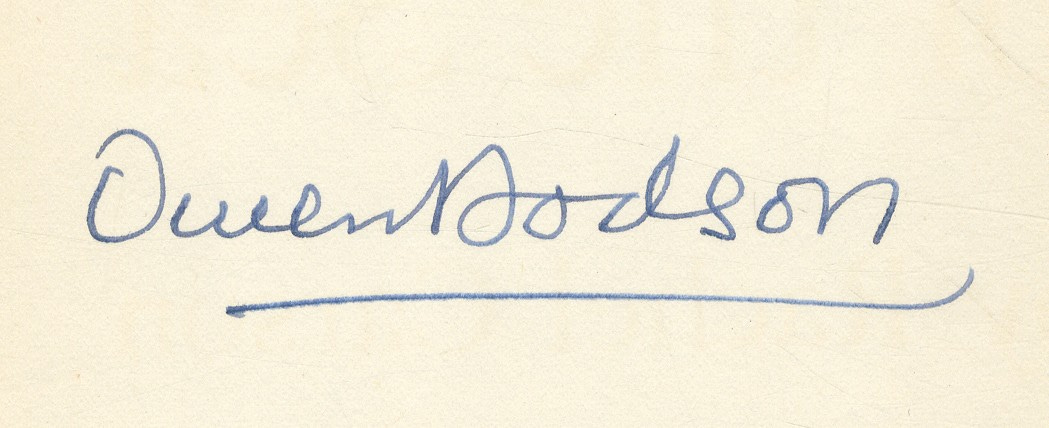

Owen Dodson (1914-1983)

I recently encountered the exceptional poetry of Owen Dodson for the first time.

Soon after, I discovered his works are, tragically, out of print, and hard to lay one’s hands on (but I found a way—I’ll list resources at the end).

A poet, novelist, and playwright, Dodson had an MFA in drama from Yale and was a professor and chair of drama at Howard University. He was also gay.

One of his plays was performed at Madison Square Garden when he was just 30 years old. So he was already a rising star when he published his debut book of poems, Powerful Long Ladder, in 1946, at around age 32.

Dodson’s poetry covers classic themes like love, grief, and injustice, and is utterly surprising; his poetic voice is sonorous, his turns of phrase quietly stunning.

In the poem “Drunken Lover” Owen writes of being too drunk to have sex, humorously describing that “stagnant hour” “when the unfulfilled is unfulfilled.” He recalls being a teenager and dreaming of what lovemaking would be like one day—then makes a comparison to the disappointing reality:

What I pictured so lovely and spring Is August and fungus calm.

In another poem, “That Star,” he declares his love will be everlasting, despite the fact that he is

[...] as mortal As Christmas in war

And while we’re on the topic of war, in his poem “Wedding Poem for Joseph and Evelyn Jenkins” is this quatrain:

Every war is a condition of love: Love for gold in the pocket Or land in another land, Or liberty where you stand.

“Wake up, boy, and tell me how you died”

Dodson was in the navy in 1942, a time when segregation meant service members of colour were divided from white service members—with barbed wire.

At one point, one of his brothers-in-arms had recently been killed in the South Pacific, and a friend’s brother had just been lynched in Mississippi.

Spurred by all these horrors and by a dream he’d had, Dodson wrote a poem, “Lament,” which speaks directly to the Black man who’d just been murdered by a racist white mob. It begins:

Wake up, boy, and tell me how you died: What sense was alert last, What immediate intuition about us You clutched like a bullet when your nails Dug red in your yellow palm And that map the fortunetellers read (this line for money, this for love) Childish again and smeared.

His descriptions can be thunderously, delicately grotesque. The bridge from which the young man was hanged

folded into mud like an old obscene accordion. The narrator vows he will now

give up all nature including grass, the second crocus, the cotton stem with the dry head,

and asks in anguish,

Must I here give you up, my friend, To wander where I wander to barbed wire crossed at intervals like Evil stars?

I recommend listening to him read this poem—he begins at 2:35 here.

In that audio file, after reading “Lament” he goes on to read “Sorrow is the Only Faithful One,” another poem written while behind that segregating barbed wire in the navy. It’s full of an almost visceral pain that’s been tempered, wrested into clean, stacked tercets.

Five lines from it:

But I am less, unmagic, black, Sorrow clings to me more than to doomsday mountains Or erosion scars on a palisade. Sorrow has a song like a leech Crying because the sand’s blood is dry [...]

The Harlem Book of the Dead (1978)

(TRIGGER WARNING: A vintage photo at the end of this section depicts a dead person in a coffin with flowers.)

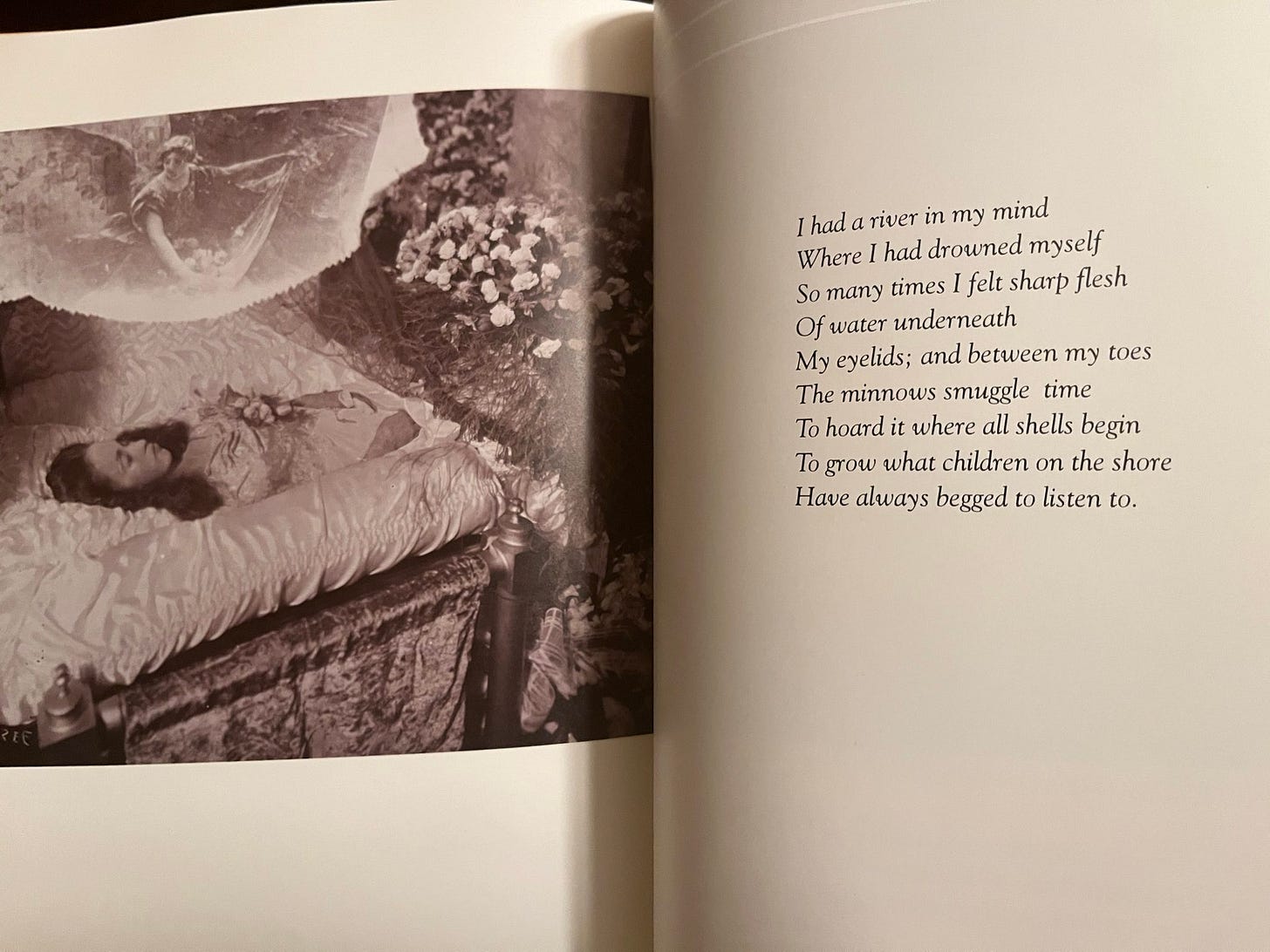

Five years before his death, Dodson collaborated with James Van Der Zee (a photographer) and Camille Billops (an artist and filmmaker) to make a super unique book that weaves together oral history, local history, poetry, art, and storytelling.

Van Der Zee had photographed the dead in Harlem for much of his life—he specialized in portrait photography, which meant he was often hired to take formal portraits of the dead laid out in their coffins. These served as keepsakes for family members to cherish.

Billops interviewed Van Der Zee when he was in his 90s and wove their fascinating conversation throughout the book. And Dodson? He wrote small, untitled poems to accompany the photographs from Van Der Zee’s portfolio.

These poems are quite diverse—sometimes humorous, sometimes oddly cloying, often thrillingly poetic, with his trademark quality of surprise.

Most take the form of wee floating persona poems, written in the (fictional) voices of the dead (though he would have mostly had very little contextual information about the individuals in the photos, as is made evident by how little Van Der Zee recalls about each photo when asked in the interview).

A poem about a serviceman opens thus:

I loved life like a budding broad I never had the nerve to kiss.

Another muses about the trappings of a funeral, and closes with a final, exquisite line:

With our veils, Our tears, Our flowers, food, The hearses that are elegant, The singing that kills the flowers.

Some poems are curious, even mysterious. One photo shows a dual funeral with two adults in two separate coffins; Van Der Zee recalls that they were a brother and sister who unexpectedly, and separately, died the same week.

Dodson’s accompanying poem reads (in full):

We grew so far away from each other

And got lonesome. Please was

Our only vocabulary.

Now and again: Will you be with me please.

A word with a vegetable sound:

Please... In the below photograph from the book is one of two curious poems that each refer to dangers that dwell within the narrator’s own mind—in this one, it’s a river; in the other (not pictured here), a scorpion.

(The final, satisfyingly weird couplet in the scorpion poem is, “Are you my scorpion / Or my champion?”)

How to access Dodson’s work

Since his work isn’t in print, you’d need to pay a pretty penny for most used copies. But if you want to find more of his work for free, you can:

Visit this Library of Congress audio recording of him reading 22 poems in 1960.

Make a free account on the Internet Archive, where you can “borrow” books to read in your browser for one hour at a time. You’ll find:

Powerful Long Ladder (1947), his first book of poems

Boy at the Window (1951), a novel

Many of his plays, contained within anthologies—including reportedly his favourite of his works (or so says Britannica), “The Confession Stone”

His biography, written by James V. Hatch

Ask your local library to find a copy of it via interlibrary loan

Dodson Wisdom

Dodson makes some great comments in that 1960 audio recording.

On waiting years to send poems to magazines, he explained:

I like them to season a little bit.

He also remarked:

“I’m going to take time out maybe this Christmas and give myself the luxury of rejection slips.”

Writing Challenge

So that’s your prompt this month:

Give yourself the luxury of rejection slips!

In other words, submit some poems to poetry journals. If you wish, let me know where you’ve submitted! And/or list your latest rejections.

My most recent rejections were from a publishing house, three contests, and a residency:

Luxuriousness.

Thank you for introducing me to Owen Dodson; what a remarkable person and I agree with your notes about the surprising and thunderous turns of his writing!